What’s it Worth?

All walks of life have expensive sides. If you’ve ever spoken to anyone about watches or art, you’ll have some idea that items you wouldn’t pick out of a skip can be worth serious wedge, and the musical instrument universe is heaving with examples of this very notion.

In this article, I’m going to have a look at the value the musical community places on certain things, the preconceptions that go with that, and the pros and cons of such a thought process.

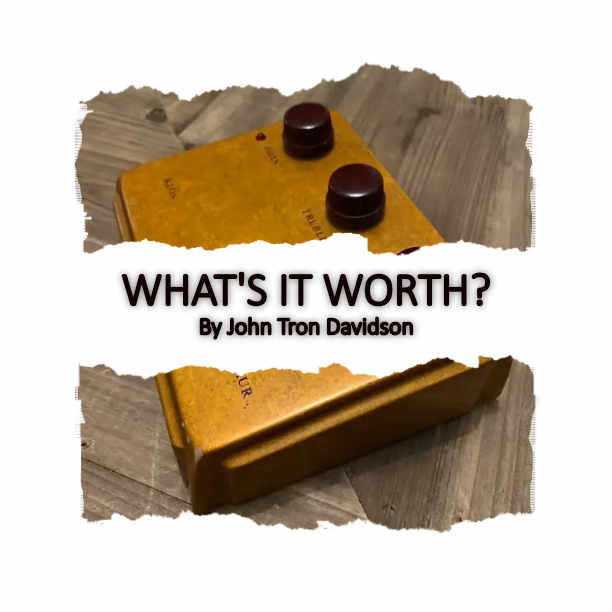

Let’s start with the obvious stuff – Klons and Dumbles. There’s really no way that an overdrive can be worth £1000, or for an amp to fetch north of $70,000. Even in the most extreme cases of celebrity ownership with full provenance, like John Lennon’s Imagine piano – which sold for $2.1 million – instruments like these are straight-up collectors museum pieces, not purchased for gigging with or humping about in a van. Crossing into the art realm completely changes the value of something owing to the nature of that collectors environment. When it comes to the Klon and Dumble, these are things that the people who buy them want to use, and it seems absolutely insane to chuck a years’ salary at an amp which can’t have cost that much in parts or man hours to make. Bill Finnegan, designer and builder of the Klon Centaur, openly reviles the fact that his pedals now fetch the sort of money that they do, so why do we do this?

The core of this is very simple, the same reason players like sparkle finishes, unique paint jobs and celebrity association – being special. There’s nothing wrong with that, and even though two players with identical setups won’t use them the same way or sound the same, we still want to have equipment that marks us apart from others, that makes our pals draw breath when we reveal the year, output or wattage of whatever it is we’re talking about. More than that though, there’s a real belief that equipment from a particular time is automatically brilliant, and while many seasoned players will scoff at such a notion, it’s worth remembering that the majority of people don’t know that a lot of ‘70s Strats were absolute hounds, or that Gibsons have notoriously fragile headstocks. The number of people I’ve seen sit down with howlingly bad guitars – especially from the ‘60s and ‘70s – and declare them to ‘play like butter’ or that they’re ‘just the best’ would make your brain collapse, and this isn’t something that’s likely to go away.

Vintage guitars, as is often reported when discussing such matters, really weren’t a thing until the ‘90s, when all your grunge lads rocked up with Strats and Mustangs that sounded terrific. It’s odd in retrospect that such a garage-level movement could facilitate such a change in attitude, but it’s worth remembering that during the ‘80s, aside from your Knopflers and Edges and so on championing the Strat – though Knopfler was into Schecters at this point – the prevailing winds were for new instruments, and interest in the old stuff didn’t manifest until your McCready’s and Gossards starting coming out with the big tones: Robin Guthrie of the Cocteau Twins tells the story of picking up ‘60s Fenders in the ‘80s for next to nothing, flogging one a year now they’re worth the same as a new BMW.

Being old doesn’t make something better by default. Older pickups can sound deeper and more harmonically rich than new pickups because of the natural process of fusing that occurs over time with their windings, but there’s no guarantee those characteristics will work for you. The same goes with the feel of the instrument itself – I’ve watched hundreds of players pick up ‘70s guitars and be crestfallen at how ordinary they are. There’s an expectation that a period or brand will be like playing a piece of the true cross, with impeccable fluidity and unrivalled, celestial tone simply because of what it is.

So, you’re thinking, this is all pretty negative, but a few major things have happened as a result of pedals, amps and guitars being priced at ridiculous levels. Big numbers and the associated shock brings interest from outside the guitar world (“Clapton’s Blackie Sells For $1 million!”), as everyone can understand the money. There’s been a greater acceptance of newer builders in the face of mental vintage prices, and more and more smaller companies are getting a chance that they might never have had. Making peace with the fact that many players may never own the vintage guitars they’ve heard so much about, opens up the playing field, moves the industry forward, encourages new ideas, and further expands the language of the instruments.

There’s now a much greater understanding of everything’s worth, perceived or otherwise. It was the internet that really changed all of this, by letting people interact, thereby whacking prices up, and pricing vintage things into oblivion. Nowadays you’re much more likely to research whatever you find, and bargains are mostly found because the sheer amount of stuff floating about online means that certain things slip through from time to time. None of this should discourage you from seeking out your own special find, but remember to physically try things whenever possible, and determine what it’s worth to you!

John Tron Davidson